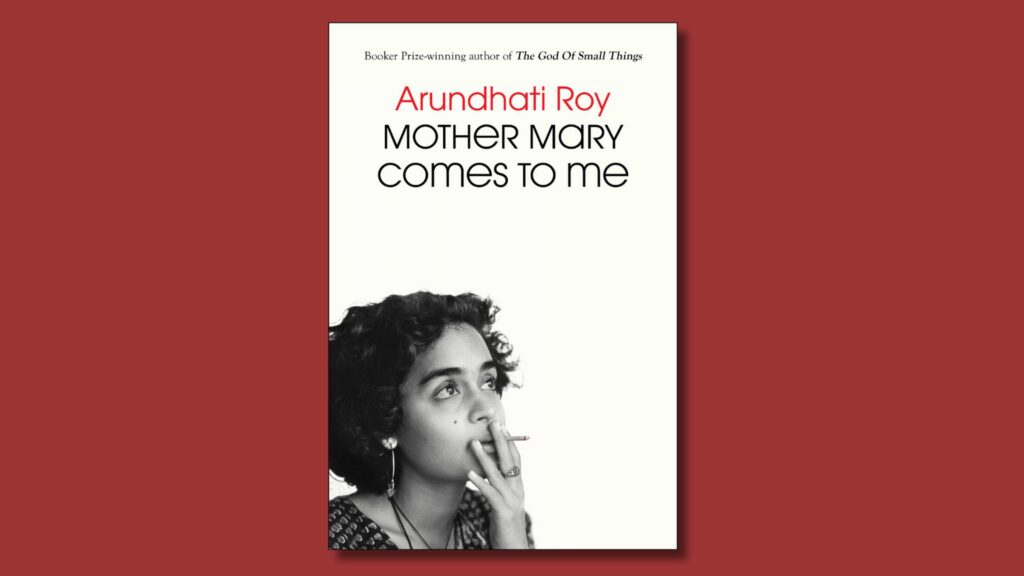

I began reading Mother Mary Comes to Me by Arundhati Roy with extra care. A signed copy rested in my hands, which made the experience feel quietly personal. It is a deeply intimate book, and I felt that closeness from the very first pages.

A Daughter Faces Her Shelter and Her Storm

In the song “Let It Be,” Paul McCartney recalls his mother appearing in a dream and offering calm advice. Arundhati Roy writes about a mother who offered no such calm. Her mother never told her to let things be. That contrast sets the emotional ground of Mother Mary Comes to Me, Roy’s first memoir.

The book arrived in September 2025. Roy wrote it after the death of her mother, Mary Roy, who died in September 2022 at age eighty nine. Roy describes herself as heartbroken and puzzled by the force of her grief. She left home at eighteen, not from lack of love. She left so the bond could survive.

The Force That Shaped Her

Mary Roy lived with fierce will. She fought a social order that limited women in money, property, and daily life. She built a well known school and ran it as owner and headmistress. In 1986 she went to the Supreme Court of India and won equal inheritance rights for Syrian Christian women in Kerala.

Her strength did not make her gentle. Roy recalls harsh words and repeated commands to leave the house, the car, even her life. Mary suffered from chronic asthma and used the threat of an attack to control her children. Roy later said her mother felt like an airport with no runways. Landing never felt possible.

Roy saw more than anger. She saw a woman clearing space for other women. That effort carried meaning even during painful moments. Roy writes that she often felt like the parent, always trying to read her mother’s moods. The effort drained her, yet the admiration stayed.

The Writer Takes Shape

After her mother’s death, Roy wrote that she mourned not only as a daughter but as a writer who lost her most gripping subject. She calls her mother both gangster and guardian. Shelter and storm lived in the same person.

Readers know Roy for The God of Small Things, which won the Booker Prize in 1997. Few know she trained as an architect first. She acted and wrote scripts before her debut novel drew global attention.

The memoir links closely with that novel. The character Ammu draws from Mary Roy. Roy’s uncle, G. Isaac, inspired Chacko, a Rhodes scholar who fails to meet his promise. Roy recalls her mother asking for a place in the book. Roy agreed without hesitation.

Family, Power, and Public Life

The memoir studies two strong women and the strain between them. It tracks family ties across siblings, spouses, and generations. It faces inherited violence and the long reach of colonial rule. Roy writes about language, class, religion, and state power in India.

She addresses pressure on Indigenous groups, Sikhs, and Muslims. She writes about dams, land, free speech, and war in Kashmir. These themes sit beside private memory and give the book wide scope without losing focus on the mother and daughter.

The Shape of the Writing

Roy avoids straight chronology. She circles memories and returns to them with added detail. That pattern mirrors the way memory works in daily life. Love between parent and child rarely fits a neat sequence.

Her English carries rhythms shaped by Malayalam speech. The tone shifts from sharp irony to quiet sorrow within a few pages. Critics praised the book for empathy and clear social critique. Many described it as a major work of memoir.

Reception

The book reached the finalist list for the Kirkus Prize. Literary Hub named it one of the most anticipated titles of 2025. Shelf Awareness praised its clarity and self examination. Reviewers noted the portrait of a mother who recognized her daughter’s writerly heart.

More Than a Story About a Parent

The memoir studies difficult love and the price of freedom. Roy writes that she spent years managing the bond and shaped herself to handle it. After her mother died, that shape felt strange without its reason.

Mary Roy appears full of contradiction. She protected with intensity and demanded with equal force. The same traits wounded and strengthened her daughter. Her refusal to follow convention set a model that Roy later followed in her work and public life.

Why the Book Matters

This memoir carries the scale often found in Roy’s novels such as The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. It honors hard love and personal freedom without softening the conflict between them.

Readers who want to understand Roy will find clear answers here. Readers facing strained family ties will recognize the emotional truth. Roy shows that telling the truth about those who formed us stands as one of the deepest acts of love.